Opinion: Egypt probably is different this time

If Egypt’s government can stick to its reform plans the country stands a good chance of resolving some of its most persistent challenges

To a Republican president like Ronald Reagan “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help”. To a financial market investor, the most dangerous words you will ever read are “it’s different this time”. These are the words that suck you into overvalued crowded trades just before they pop. The wise investor often is the cynic who sells on this headline.

At a country level, there is one major exception to this rule, and that is when a country makes the transition from historic poverty into industrialization and wealth. No-one today worries about famine in China, a problem that killed millions as recently as the 1960s. India, a country too illiterate to industrialize until 2010, now sees Foxconn moving Apple iPhone production there from China. Both countries really are different this time.

Fertile ground for growth

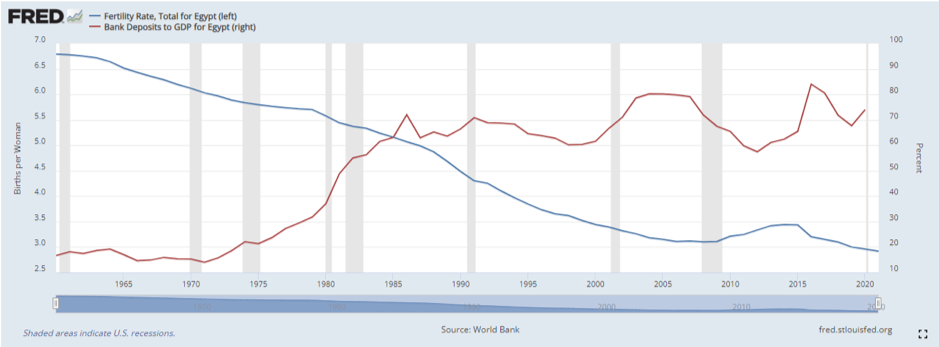

Egypt is the next to make that transition. It requires 70-80% adult literacy (achieved by 2010), electricity (sufficient was available already in the 1980s thanks to Soviet style economic policies and hydrocarbon investments) and a fertility rate below three children per woman. Low fertility allows families to save money in banks, which drives up the supply of money (bank deposits) and cuts the price of money (interest rates).

The UN expects Egypt’s fertility to drop below three in 2025-2029 and President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi is encouraging this decline. This shift should let Egypt self-finance much of its own growth. It can become a typical 21st Century emerging market. Within a few decades, foreign currency borrowing out of Egypt may be as rare as net eurobond issuance out of Brazil is today.

Yet Egypt already has the highest bank deposits in the world of any country with a fertility rate above 3.0, averaging about 70% of GDP since the early 2000s (it was already over 60% from the 1980s thanks to the hydrocarbon sector). This is most likely because fertility has been fairly close to three since the 2000s. This is not as good as Morocco, which did see fertility drop below three in the early 2000s, and where bank deposits have grown from 40% of GDP to around 100% of GDP, helping keep interest rates very low and fostering industrialization.

But Egypt has done well enough to ensure its bank deposits are a similar ratio as the Philippines, and considerably more than Indonesia. So why aren’t its interest rates already as low as those Asian success stories?

The answer is public sector borrowing. This has often sucked up nearly all of the banking system’s deposits, and Egypt has regularly borrowed offshore because even that has not been enough. Excessive spending has often contributed to current account deficits, leading to devaluations and debt crises.

Ronald Reagan could have been referring to Egypt given the public sector’s historic tendency to spend and borrow. In 1876, two-thirds of government revenues were spent servicing its debt and Egypt was forced to sell shares in the Suez Canal to the UK. In 2024, again two-thirds of Egypt’s revenues have been allocated to interest expenses. This time, Egypt has sold a majority stake in a tourist resort, similar in size to Mykonos, to the UAE’s ADQ, to help it get through a debt crisis.

Why might Egypt be different this time?

Given 150 years of an apparently unchanged story, why might Egypt be different this time?

As noted above, the fertility rate decline will be a key driver. It provides more supply of cheaper local funding. And it comes when the government has already shown a decade-long commitment to cut its demand for borrowing.

The Arab Spring period from 2011-13 were Egypt’s worst fiscal years since 1999 (based on IMF data) with a primary budget deficit averaging 5% of GDP. The post-2013 government slashed this to 2% of GDP by 2017 and has achieved primary surpluses since 2019.

This positive story was concealed by a public debt inheritance that is very high at around 90% of GDP. When global interest rates, and Egypt’s own rates soared after the Covid pandemic, the high debt level combined with higher interest rates meant the headline budget deficit exploded from 5% of GDP to 11% of GDP (IMF October 2023 figures). Such high levels of borrowing squeezed out private sector investment and led many to fear Egypt would default.

We invested in a large overweight position in Egypt’s external debt because we recognised the underlying improvement in the primary balance, and because we were increasingly confident in 2023 that international support for Egypt would be forthcoming and very large.

In the event, the UAE’s $35 billion real estate investment surprised even us. But other support was already flagged in 4Q23. The IMF upped its package to $8 billion, the EU is providing $8 billion and the World Bank $6 billion. The total package of $57 billion, roughly 15% of GDP, is one of the biggest totals to an emerging market we’ve ever seen.

This has seen Egypt’s Eurobonds rally very hard. Default risk has plunged, from the 50% priced in as of February, to sub-30% now. Egypt’s banking system, which is long government debt, looks safer and so equity prices have jumped.

The exciting trade today, which we are participating in, is to shift from external debt to buy local currency government debt. In March, the interest rate on t-bills has eased from 32% to sub-29%. With an appreciating currency, that provides a very appealing US dollar return.

Reaching a turning point

Egypt is in much better shape than after previous near-defaults. It can industrialize and grow the sectors that bring in foreign exchange, so helping it avoid future current account problems, while falling fertility means its supply of local funding is set to rise significantly, helping on the budget side.

Egypt’s twin deficit problem will improve like many other mainstream emerging markets over the last 20 years.

There are signs of improvement already in Egypt’s current account receipts. In 2017-18, there was no Egyptian merchandise export category earning more than $1 billion each year except for crude oil ($5 billion) and petroleum products ($4 billion). By 2022/23, there were three more. Crude oil was down to $2 billion, but petroleum product exports had soared to $11 billion, fertilizers topped $2 billion and both ready-made clothes and organic chemicals were $1 billion each. Cotton textiles and household electrical appliances were each near $1 billion too.

Tourism revenues are expected to grow strongly. Photo: Jamal Saidi/Reuters

Tourism has already seen the rolling 12-month total of $14 billion (4% of GDP) exceed the $13 billion pre-Covid peak. The UAE investment of $35 billion mostly for one tourist resort, suggests far higher numbers are likely in the coming decade or two. It is not hard to imagine good value tourist resorts bringing in 5-10% of GDP over the long-term.

Foreign direct investment, except via the Gulf investment in tourist resorts, won’t come so quickly. Most FDI investors who commit to a country for 10-15 years when they build a factory so they want to see three years of stability (political, economic and financial) first. Greenfield manufacturing from FDI is probably a 2027 story at the earliest. But privatization can help accelerate this, when good assets are put on the block. In the meantime, the $57 billion package has bought Egypt time to see manufacturing take off.

Can Egypt turbo-charge its benign future? Yes, by encouraging more female participation in the labour market. Those countries that have delivered the very highest GDP growth rates in recent decades have labour force participation rates around 80%, nearly double that of Egypt. From Turkey to Saudi Arabia, countries are showing the GDP growth benefits of improved gender equality.

But in our view, Egypt is already on track for a much better future. It simply needs to stick to its fiscal plans, retain a competitive EGP, maintain the social peace and extend welcoming arms to foreign and domestic investors willing to invest in Egyptian assets.

Charlie Robertson is head of macro strategy at FIM Partners